In previous articles we talked about Roman Zaragoza and Visigothic Zaragoza. In this article we will focus on Muslim Zaragoza, known in its time as Saraqusta or Medina Albaida (the white city), and more specifically on the various ethnic groups and religions that inhabited it.

During the Muslim rule in Saraqusta, which lasted from 714 to 1118, 3 religions and as many cultures cohabited. This religious and cultural heterogeneity created differences between the 10,000 inhabitants that Zaragoza had at the beginning of the 8th century and between the 25,000 inhabitants that it had in the middle of the 11th century. In this article we will review the history of Saraqusta through these various religious and ethnic groups.

The saraqusti muslims

After the Islamic conquest of Zaragoza, many of the inhabitants of Zaragoza will be Muslims. However, the group of Muslims was not homogeneous. There were many differences in social status and ethnicity between them.

The arabs of Saraqusta

Islam was born in Arabia, Allah chose an Arab as a prophet to reveal his message, said message was revealed in the Arabic language and it was the Arabs who took care of expanding this religion during its first 100 years of history. These facts made the Arabs feel legitimate to rule over other ethnic groups that had converted to Islam at a later date. And in Saraqusta it will be so, the ruling class was the Arabs during almost 400 centuries of Muslim domination.

Within the Arabs there were also differences and conflicting ethnic groups. In Saraqusta the Arab tribe that ruled in the 8th century was the Kalbi or Yemeni Arabs. These Yemeni Arabs built the Zuda fortress, which was attached to the wall and the Ebro river. This fortress served as the residence for the governor of the city. Currently we only preserve the tower from that fortress.

The Kalbíes, both in Zaragoza and in the rest of Al-Andalus, always maintained a certain rivalry with another Arab tribe, that of the Syrian Arabs or Qaysíes. These qaysíes presumed to be genealogically closer to Muhammad. On the other hand, the Kalbíes boasted of having a more glorious past than the Qaysíes before Islam, since these, the Kalbíes, created ancient kingdoms such as Saba at a time when the Qaysíes were still nomadic tribes without organization.

The most tense moment between the Kalbíes and Qaysíes that was lived in Zaragoza happened in 750 when the walí of Al-Ándalus Abd al-Málik sent a Qaysí to Zaragoza to act as governor there. The Kalbíes rebelled against the Qaysí governor, overthrowing him in 753.

The kings of Aljafería

After the fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba in 1031, the Taifa kingdom of Saraqusta was created. Two Yemeni dynasties came to reign in Zaragoza. The first dynasty was the Tuyibí (1018-1038) and the second dynasty was the Hudí (1039-1110).

During the reign of Hudi Al-Muqtádir (1046 – 1081), the Aljafería Palace was built, the new residence of the Saraqusta sultans. A multitude of mathematicians and astronomers attended the court of this Muslim king, turning Saraqusta into a city of sages.

Berbers “second class Muslims in Saraqusta”

In the IX century they were the lower class of the Muslim conquerors. They were an ethnic group originating from North Africa. The Berbers converted to Islam with the expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate.

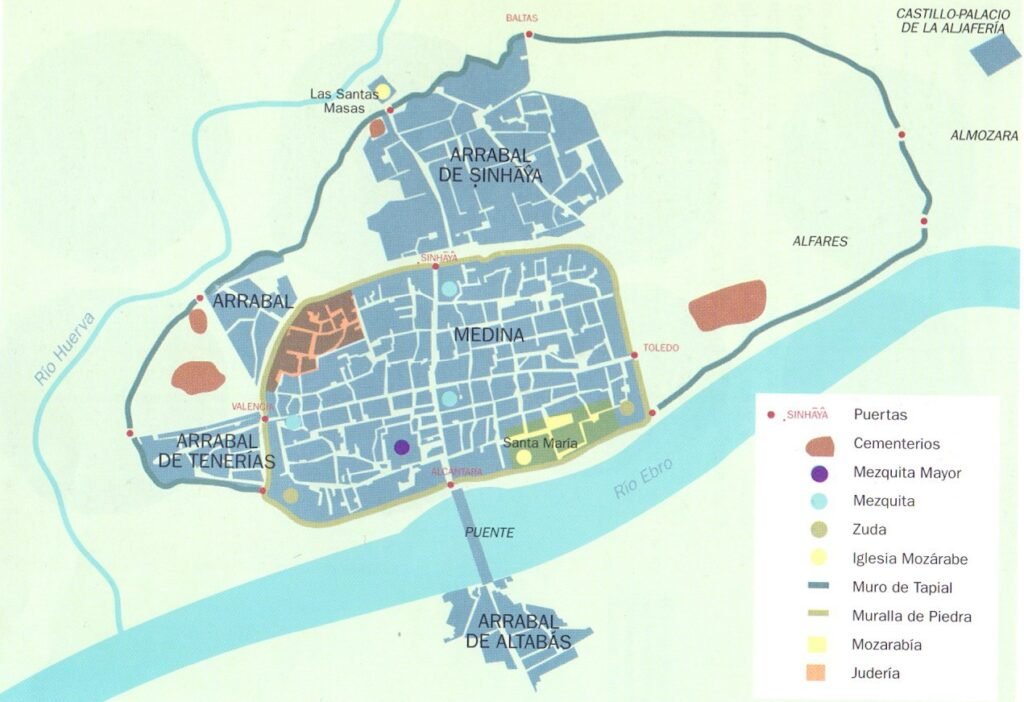

The Saraqusta Berbers lived outside the city walls. In 2001, when the Paseo de Independencia was excavated with the intention of building an underground car park, the archaeological remains of the neighborhood where the Berbers of Saraqusta lived were discovered.

The Almoravids “the Berbers who defended Al-Andalus”

Although during the early period of Al-Andalus the Berbers were submitted in most cases to the Arabs, from the 11th century they were to be the protagonists in the defense against the reconquering Christians when the Almoravids entered the peninsula.

These were Berbers originally from the south of Morocco and maintained a more rigorous interpretation of Islam than the Andalusian Arabs. They took over Zaragoza in 1110, overthrowing the last Hudi king of the city, Abdelmálik.

However, the Almoravids only ruled Saraqusta for 8 years. In Muslim Zaragoza they are remembered for giving Avempace the position of vizier. Avempace was a Saraqusti sage known for introducing Aristotle’s philosophy to Western Europe a century before St. Thomas lived.

The muladíes of Zaragoza

The muladíes joined the Muslim population of Zaragoza. These were Hispano-Romans or Visigoths who decided to convert to Islam after the Islamic conquest. The main advantage of converting to Islam was fiscal. The dimmníes (Christians and Jews) were forced to pay a tax called “jizya” that was much more burdensome than the one paid by Muslims, “zakat”.

The muladíes became the largest group in the city. They spanned the entire social spectrum. There were those from the humble class and others who came to prosper occupying positions of relevance. In Zaragoza a muladí family, the Casio, ruled from 802. They became known as the Banu Qasi after converting to Islam and Arabizing.

The Banu Qasi were related to the royal house of Pamplona and came to rebel twice in the middle of the IX century against the emir of Córdoba Abderramán II. On both occasions the Banu Qasi were defeated, but obtained the pardon of the Emir of Córdoba.

Mozarabs of Zaragoza

Christians who decided to maintain their Christian faith while living in Muslim territory were known as “Mozarabic”. Although in the VIII century they were the majority of the inhabitants of Zaragoza, they progressively decreased due to the tax advantages that converting to Islam entailed. According to historian Richard W. Bulliet, in the 12th century (when the Christians reconquered Zaragoza), the Mozarabs were less than 10% of Andalusian society. It should be noted that the Mozarabs, although they preserved the Christian faith, were Arabizing their customs and language, even forgetting their Romance languages.

According to the XVI century Zaragoza historian Jerónimo Blancas, the Mozarabs of Zaragoza had their neighborhood located in the northwest of the city. That is, between the fortress or zuda and the church of Santa María (The Church of our Lady of the Pillar). Some historians also point out that some Mozarabs also lived around the Church of the Holy Masses (where the Basilica of Santa Engracia is currently located).

Zaragoza jews

According to historians such as Sánchez Albornoz, they collaborated with the Muslims in their invasion of the Iberian Peninsula. This is due to the fact that they were persecuted in the last period of the Visigothic kingdom of Toledo and the Islamic invasion meant that they were equal to the Christians under the status of dimmníes.

In Zaragoza, an aljama (Jewish autonomous entity) was located in the southwestern part of the old Roman enclosure. The epicenter of the Jewish quarter of Zaragoza corresponds to the current Plaza San Carlos and the Mayor Synagogue occupied the place currently occupied by the Royal Seminary of San Carlos Borromeo in front of the Casa de los Morlanes.

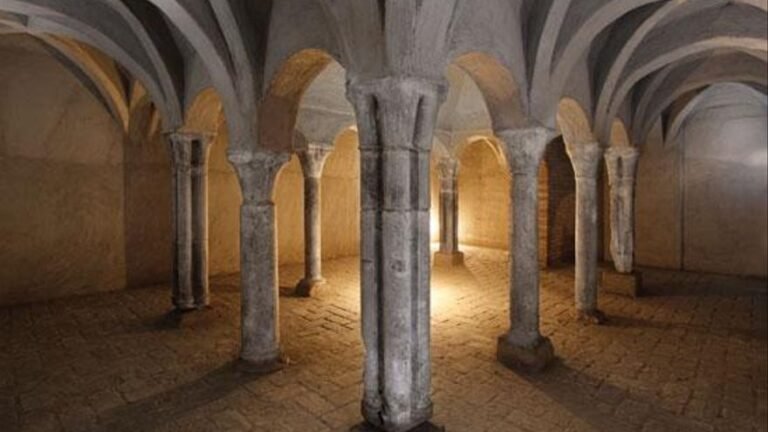

The only archaeological remain we preserve from the Jewish quarter of Zaragoza is a few Jewish bath that is located at 126 – 132 of the Coso street. Jewish ritual baths were held there.

In Muslim Zaragoza there were Jews who obtained positions of great relevance in the city government. The most emblematic case was that of Yekutiel ben Isaac, this guy reached the dignity of vizier, during the reign of Mundir II (1036-1038).

Bibiliography

Guzmán, R. M. (2003). Los grupos étnicos en la España musulmana: diversidad y pluralismo en la sociedad islámica medieval. Revista Estudios, 17, 169–215. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5761967

Lasala, J. A. S. (1993). Cronología y gobernadores de Zaragoza omeya. Aragón En La Edad Media, 10, 843–858. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=108482

Giménez, D. (2021, March 8). La desaparecida judería de Zaragoza. Zaragoza Guia .com. https://zaragozaguia.com/la-desaparecida-juderia-el-barrio-judio-de-zaragoza/